By Geoffrey Thomas

Published Wed Sep 11 2024

Never in the history of commercial aircraft manufacturing has a company squandered so many opportunities to launch a compelling design that the airlines wanted as McDonnell Douglas did over the concept of a wide-body twin-engine aircraft.

There is little doubt if it had launched such an aircraft it would still be in business today and be a dominant force.

Over a period of just over 30 years first Douglas, and then McDonnell Douglas, studied and rejected an incredible 33 designs and sub designs for a market that has since been filled by 8,501 A300, A310, A330, A350, 767, 777, and 787 aircraft either delivered or on order.

The sorry tale starts as far back as 1966 with the Model D-960, 62, 63, and 66, all studies to meet American Airlines' famous “Kolk Machine” to fly 250 passengers from La Guardia to Chicago.

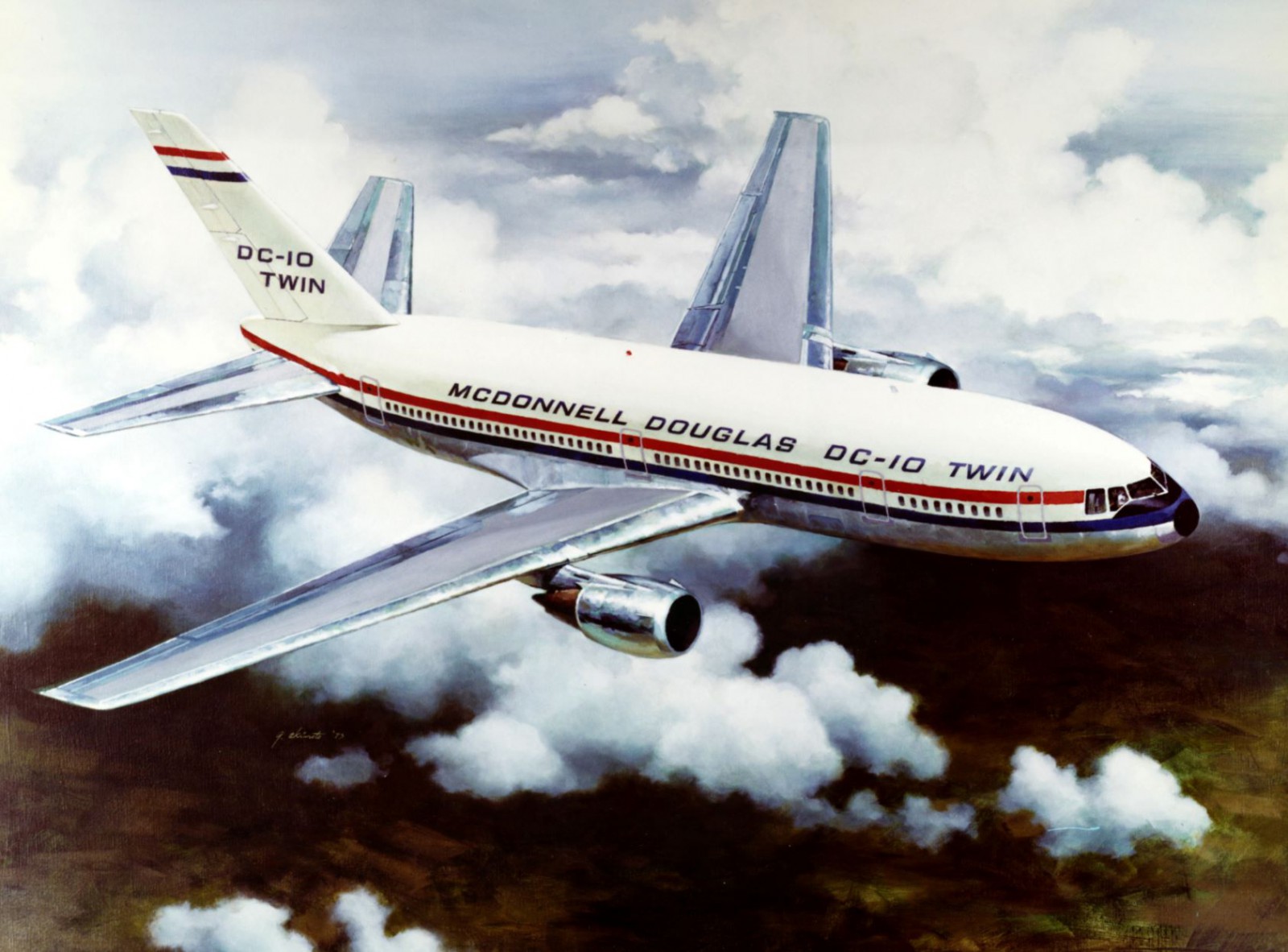

That study morphed into the three-engine model D-967, which became the DC-10 in 1967. But as early as 1968 the twin had re-emerged as design Model D-969 with minor variations through till 1973.

It was dubbed the DC-10 Twin. During that year there were several major versions; D-969C-13, 300 inches shorter, C-14 with 224 inches less, and C-10 with 344 inches and the C-15.

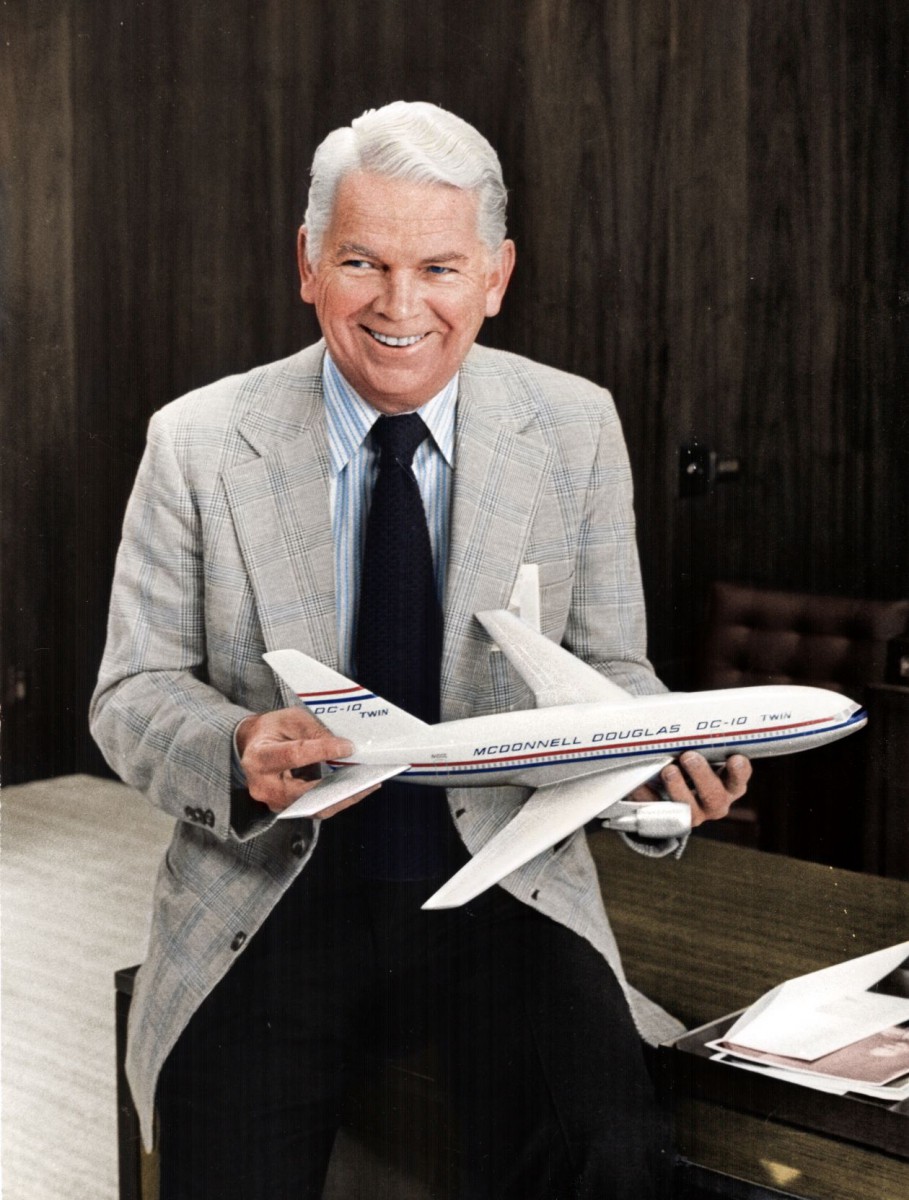

According to John Brizendine, who was President of Douglas from 1973 through 1982, James McDonnell, Chairman of McDonnell Douglas (Mr Mac) approached Airbus with a proposal that Airbus and Douglas combine on a 50/50 basis to produce a big twin based on the DC-10 cross-section. Mr Brizendine recalls that Airbus President & CEO Henri Ziegler told Mr Mac “France must have its own.”

Mr Ziegler, as a war hero, resistance fighter, and chief of staff of De Gaulle’s Free French forces in London, had become a close and trusted friend of French President Charles De Gaulle.

The French President had appointed him to rescue the Concorde project which had experienced delays and cost overruns and Mr Ziegler had convinced De Gaulle, who resented US domination of commercial aviation, to support the Airbus concept.

At the time, France was enjoying what was called Trente Glorieuses ("Thirty Glorious Years" of economic growth between 1945 and 1975). In the few years leading up to 1969, it had passed the UK’s GDP, exploded an H-Bomb, withdrawn from NATO, and become the third country to launch a satellite into orbit. France believed it was invincible.

Complicating matters politically, France was ravaged by strikes in 1968 and there was even the suggestion of civil war and the intervention of the army. Thus, there was absolutely no chance at this point that cooperation would win over pride, although Mr Mac did agree to give Airbus the pylon/nacelle design for the DC-10’s GE CF-6 engine for commonality reasons.

Spurned by France on October 4, 1971, MDC announced its DC-10 Twin jet development of the DC-10 which would be head-to-head with the A300. This aircraft was to have 89 per cent commonality with the DC-10-30 which had been widely sold in Europe and 93 per cent with the DC-10-10.

At that time, Douglas executives predicted the advent of duel rating for pilots on the two types. It would carry between 239 and 300 passengers and be powered by either the 51,000lbs GE CG6-50C or 52,000lb JT9D-57 engine. It would have a 6ft wider span than the DC-10 but be 14ft shorter than the DC-10.

The company went to considerable trouble to launch the DC-10 Twin as Lockheed was struggling with the L-1011 and the Boeing was having huge problems with the 747 and there was a window of opportunity to be the only US game in town.

MDC arranged a huge review for airlines at Long Beach of the DC-10 Twin even hiring "twins" to show off the cutaway model.

Jackson McGowan President of Douglas from 1968 to 1972 told the author in a 2004 interview that he was bullish on the DC-10 Twin but claimed that Mr Mac’s son, John McDonnell, who at the time was VP of Finance & Development, was wary of expenditure and the head-to-head competition with Airbus. The late Mr McGowan said that “the risk would have been minimal and at the time development costs were put at just $250 million.”

After a spectacular career with Douglas, Mr McGowan resigned in 1973 at the age of just 55. “I knew damn well that with the McDonnell’s influence, Douglas was not going anyplace.”

Mr Mac quashed deals that, he and David Lewis, the President of McDonnell Aircraft Company, had worked hard to put together because he felt they were too generous. Those deals may well have seen the DC-10 totally dominate the market.

READ: David Lewis could have made McDonnell Douglas the dominant player in aerospace

In a 1988 edition of the McDonnell Douglas staff magazine Spirit, the Director of Business Planning Sieg Strange said, “In the case of the DC-10, it was Jack McGowan and David Lewis trying to convince Mr Mac that there was an opportunity to literally make the DC-10 the only wide-body tri-jet. But there was a lack of understanding about how airlines made decisions, which circumvented some opportunities.”

John McDonnell’s cousin, Sandford McDonnell, who became President and CEO of McDonnell Douglas in 1972, in the same edition of the Spirit conceded that many opportunities were missed. He said that “Douglas (McGowan & Brizendine & Lewis) felt they knew how to run the commercial business better than we, their bosses, and they were probably right.”

And so, on July 30, 1973, the McDonnell-dominated board baulked at a go-ahead for the DC-10 twin. Mr McGowan maintained that “the orders were there from European airlines such as Swissair and SAS” but Mr Mac insisted on a US carrier.

In fact, the KSSU Group heavily favoured the DC-10 Twin at the time, which would have meant orders from UTA and KLM as well.

In 1975, a new jumbo twin was announced by MDC. Called the DC-X-200, it was designed for 230 mixed class passengers, which was significantly smaller than the DC-10 Twin which was to accommodate 239 to 300. It was to be 30ft shorter than the DC-10 with an all-new advanced technology wing and powered by two CF6-45, 45,000lb thrust engines.

This was based on 1974 design studies called the Model D-969L, M, P, and 969N-4. However, Mr Mac had made it very clear that risk-sharing was the only way this design would take flight.

Sandy McDonnell and Mr Brizendine toured Europe trying to build a business case for European collaboration. The British and French were responsive. MDC’s discussions with the British revolved around a Rolls Royce-powered DC-10-30R for British Airways, the building of the supercritical wing for the DC-X-200 which would feature extensive use of composites, a joint SST effort, military transport, and some missile work.

But those talks went nowhere. In France, there was more urgency. French President De Gaulle had passed away, the Airbus A300 had acquired only a handful of orders and the French Government wanted to bolster what it termed the “lagging commercial transport sector.”

In 1975, Airbus sold just 22 aircraft and incredibly only one in 1976. In the five years since its first flight in October 1972, the A300 had racked up only 38 orders and there were 16 whitetails against the fence in Toulouse.

Discussions started with both MDC and Lockheed and the former quickly emerged as the favourite. In June 1976, Sandy McDonnell announced that MDC had a definitive agreement with Avions Marcel Dassault-Breguet Aviation relating to the joint engineering, marketing, manufacturing, and support for an improved version of the Mercure.

Those talks also went nowhere and the French industry would eventually launch the all-new A320. Sandy McDonnell also announced that MDC was active in discussions to cooperate with Airbus in a way that would benefit both the DC-10 and the A300B.

At the time, most major European airlines were operating the DC-10-30 and a number had ordered a few A300s. But within months the deal was unravelling, at least publicly, as France had asked MDC to drop the larger DC-X-200.

However, while Sandy McDonnell was wining and dining European partners, Mr Mac was still signing the checks – or more to the point, cancelling them. In a October 23, 1978, Business Week article entitled “Where Management Style Sets Strategy”, Sandy recalled an incident where Mr Mac blocked a decision made by him. Sandy swiftly pointed out, “But Mr Mac, you and the board made me president last year and you’ve just made me CEO.” “That’s right”, Mr Mac responded. “You’re the CEO and I am the boss.”

According to the article in Business Week, Sandy McDonnell implied that it was Mr Mac’s influence that killed the deal with France. “Mr Mac was involved in everything and would ‘pull the plug’ instantly – this seriously affected morale.”

But for MDC, the reality was fast catching up with its dream of globalization and its goal and passion of risk minimization for the building of a twin-engine model to complement its DC-10 or any new commercial design.

Boeing announced the 767 on July 14, 1978, with an order for 38 from United Airlines. MDC also played around with D-969N-11 for American Airlines, D-969-12 for United Airlines, and even the DC-X which was to marry the A300B with the DC-X-200 wing.

Airbus also gained a “head of steam” and was able to launch its A310 on 7 July 1978 with an order from Lufthansa for 25. In all, Airbus sold 69 A300s and A310s in 1978.

In early 1979 studies continued at MDC with the D-969E and the D-969N-21E for American Airlines and the D-969N-21L with winglets. Late that year a fresh look was underway with the D969N-300 which was dubbed the DC-X-300 but it went nowhere.

In 1981, MDC lost its number two spot to Airbus and Lockheed announced the closing of its Tristar production line. For Douglas, the prospects were gloomy with no DC-10s to be delivered beyond 1982 and only 45 Super 80s to be built.

Mr Brizendine, drained from the interference by the McDonnells, decided to retire. In March 1982, Sandy McDonnell appointed GE’s VP of Marketing Development Jim Worsham to take up an EVP position at Douglas. Mr Worsham had met Sandy McDonnell during the successful campaign to sell F-18s to the Royal Australian Air Force.

Mr Worsham pioneered deals with TWA and American to at first lease, then buy MD80s and MDC was on the way back. In 1983 a larger twin model was envisaged called the D-969C-10 which was a DC-10 body plus 25 feet with 14ft added to the wingspan.

In late 1986, MDC launched a modest improvement of the DC-10 – dubbed the MD-11 – with various commitments for 92 aircraft from 12 airlines but it was a compromised design because of the decision by the MDC board not to sanction funding for an all-new wing – a fact that would come back to haunt the company.

Australia’s Qantas concurred with the opinions of other airlines when it told the author that it would not consider the MD11 because the wing had no growth potential. In 1993 MDC touted the MD-11 Twin in several versions the D-969C-115, Model U-4, and Model V-3 but to no avail as the MD-11 itself was in strife not meeting performance guarantees.

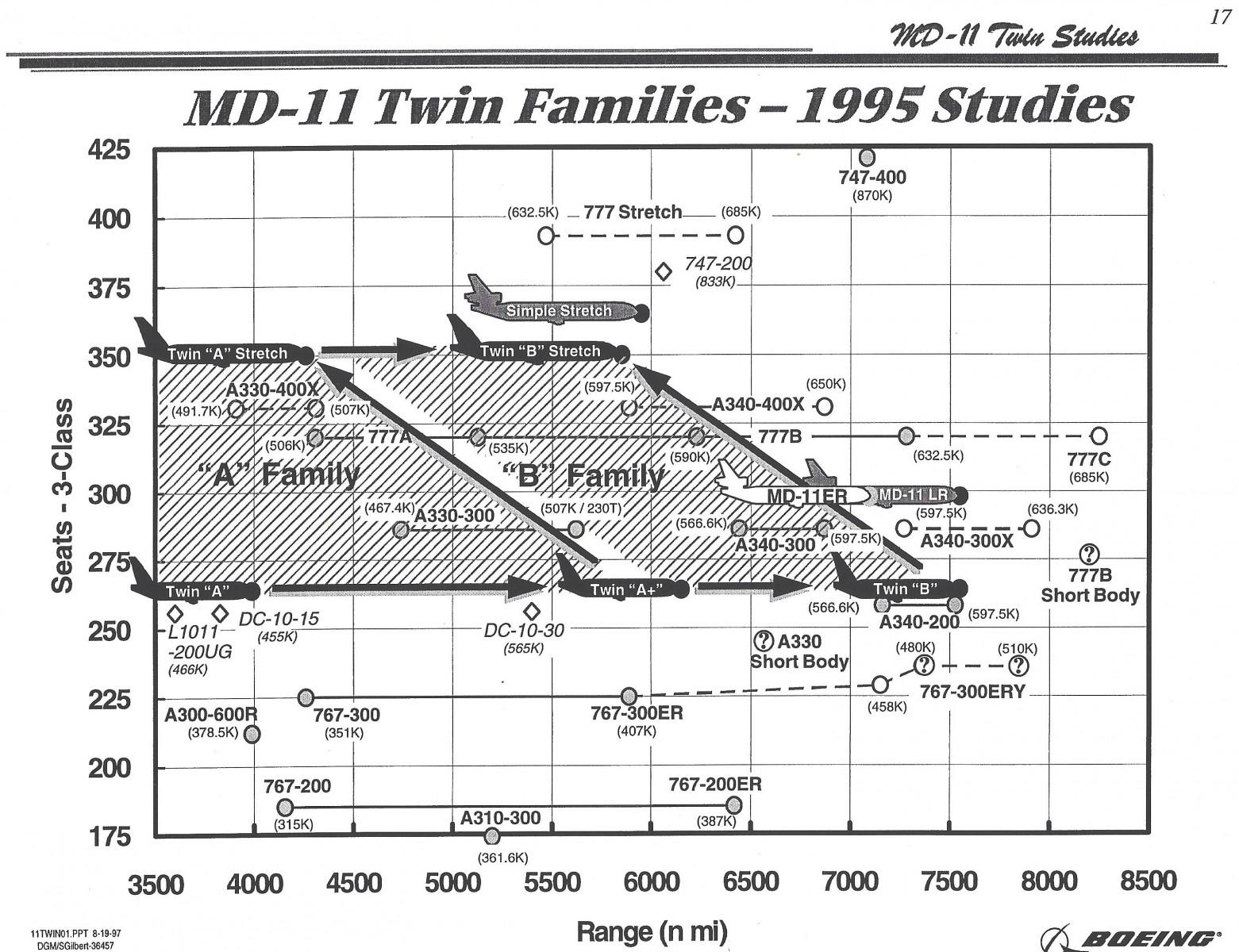

However, studies were resurrected in 1995 (above & below) with two families (A & B) and two fuselage lengths ranging from a 275 seater with a range of 4000nm up to 7500nm and a stretch that would carry 350 passengers between 4000nm to 6000nm.

The final study big twin was in 1996 with the MD-20-200 and -300. That study was based around a 767-styled fuselage with the MD-11 wing and cockpit. Four fuselage diameters were examined at 244in, 222in, 207in, and 198in.

Some suggest that this study was part of the play to get Boeing to buy McDonnell Douglas but whatever the reason like all the big twin designs before it, it stayed well and truly grounded. After the merger with Boeing, significant effort was put into seeing if MDC studies for an MD-11 Twin could be married to a new Boeing wing.

A presentation (below) was made in August 1997 which pitched the MD-11 with a new Boeing wing to fit between the 767 and 777 much as the 787 finally did in the next decade. It seems incomprehensible that the aircraft company that perfected the twin-engine aircraft with the DC-3 and then sold almost 2000 twin-engine DC-9 series did not jump into the 250-300 passenger big twin jumbo.

There was evidence by the 747-freighter load that this was the way to go but MDC’s St Louis board, by their own admission, never understood the airline market and how it worked.

It is incredible to think between 1968 and its merger with Boeing in 1997 MDC only launched ONE new aircraft - the DC-10. And in the same time frame, it only won TWO new military contracts with its own designs - the F-15 Eagle and the C-17.

A chronic lack of R&D, the resignations of top executives because of interference from Mr Mac and a lack of trust (in Douglas), and understanding of the airline market by the top management and board, killed off the premier commercial aircraft builder in Douglas and the number one military aircraft manufacturer in McDonnell.

DC-10 Twin / MD-11 Twin Chronology

Year Model

1966 D-960

1966 D-962

1966 D-963

1966 D-966

1968 D-969 (DC-10 Twin)

1973 D-969C-13 (-300 inches)

1973 D-969C-14 (-224 inches)

1973 D-969C-10 (-344 inches)

1973 D-969C-15

1974 D-969L

1974 D-969M

1974 D-969P

1975 D-969N-4 (new twin, wing)

1976 DC-X-200

1976 D-969N-11 (American Airlines)

1976 D-969N-12 (united Airlines)

1976 D-969-14

1976 DC-X (A300B plus DC-X-200 wing)

1976 D-969M

1977 D-969E

1977 D-969L-17

1977 D-969N-21E (American)

1977 D-969N-21L (Twin with winglets)

1983 D-969C-10 (+25ft body/+14ft wing)

1992 D-969C-114 (MD-11 Twin)

1993 D-969C-115

1993 Model U-4

1993 Model V-3 (new twin with Hybrid wing)

1995 Model A standard and stretch

1995 Model B standard and stretch

1996 MD-20 (six-wheel truck)

1996 MD-20 (MD-20 body plus MD-90X wing)

1996 MD-20-200/300

1997 MD-11 Twin with new Boeing wing

Have questions or want to share your thoughts?

Get In Touch